Telltale signs of SIDS: congestion, edema, inflammation, bleeding in chest - Part 1

A symptomless condition yet SIDS autopsies reveal serious internal damage

SIDS and vaccines — don’t look here folks!

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is said to occur during a baby’s sleep and has been documented as a leading cause of postneonatal death (babies between 2 months to one year) since the late 1960s. Yet, its cause is still described as an enigma. Health authorities like the CDC claim not to know what causes SIDS, but they are certain of one thing: it’s not caused by vaccines.

SIDS is the sudden, unexpected death of a baby younger than 1 year of age that doesn’t have a known cause even after a complete investigation.

Multiple research studies and safety reviews have found that vaccines do not cause and are not linked to SIDS.

The agency asserts this claim even as it admits that SIDS cases ordinarily arise at about 2-4 months of age, the same time that 2- and 4-month vaccines are given.

Babies receive multiple vaccines when they are between 2 to 4 months old. This age range is also the peak age for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The timing of the 2 month and 4 month shots and SIDS has led some people to question whether they might be related. However, studies have found that vaccines do not cause and are not linked to SIDS.

While the cause of SIDS is unknown, according to the NIH’s (National Institutes of Health’s) Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), one theory suggests a trifecta of risks that could cause SIDS.

More and more research evidence suggests that infants who die from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) are born with brain abnormalities or defects. These defects are typically found within a network of nerve cells that rely on a chemical called serotonin that allows one nerve cell to send a signal to another nerve cell. The cells are located in the part of the brain that probably controls breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, and waking from sleep. (Emphasis added.)

These three risk factors are:

An infant with an unknown gene change or brain defect that puts the child at risk of SIDS.

During the first six months of a baby’s life, s/he goes through many quick developmental phases that can cause changes in the way the body controls or regulates itself. At the same time, it is learning to respond to its environment.

Environmental stressors such as sleeping on the stomach, being overheated, and exposure to cigarette smoke are implicated as causal factors.

The NICHD acknowledges that the brain is not well understood, yet it still makes definitive claims. A critical look raises another question: why do SIDS cases only appear after two months of age, especially considering the following:

The risk factor claimed by the CDC is only theoretical.

It is unclear how normal developmental changes could lead to sudden death. In fact, one might say it is counterintuitive. By two months, and, certainly by a year, the child is much more developed than at birth. This would make it more likely that a baby would unexpectedly die soon after birth and less frequently as s/he gets older and is better able to regulate itself.

The claim that environmental stressors cause SIDS is also an assumption. By the time a baby is between four to six months, and sometimes earlier, it can turn over from stomach to back, making sleeping position less of a factor. Unless a new caregiver who smokes is introduced between two and four months, a parent or caregiver who is smoking would likely have been doing so from the time the infant is born. If being overheated while sleeping is an issue, one would expect that would be a seasonal factor not linked to a specific age range.

Because the first two situations can't be seen or pinpointed, the most effective way to reduce the risk of SIDS is to remove or reduce environmental stressors. Strategies to remove these stressors form the basis of the Safe to Sleep® campaign messages.

SIDS: A phenomenon that emerged alongside infant vaccination

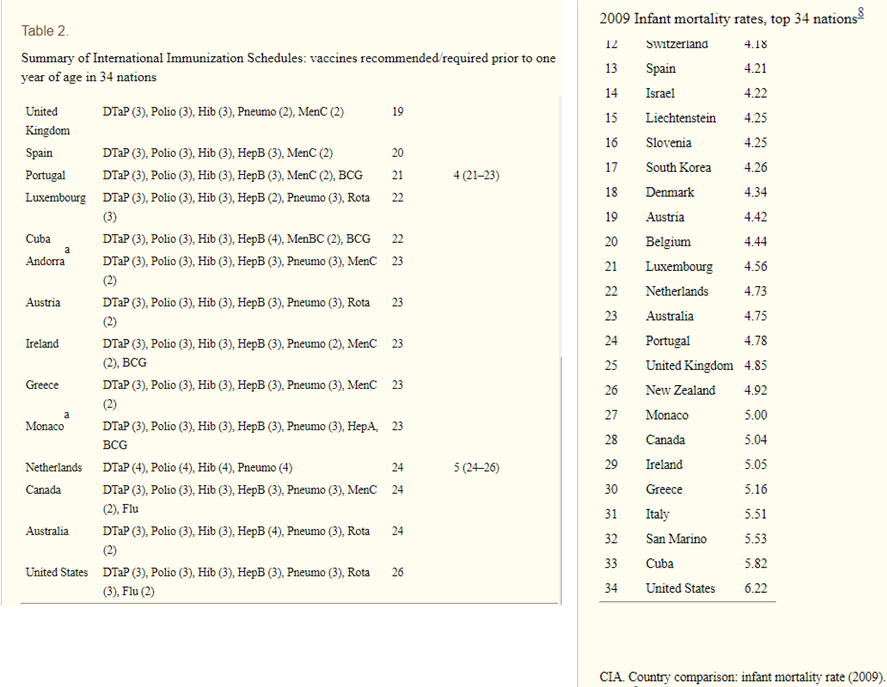

Despite the CDC's assertion, other researchers have found potential links between vaccines and SIDS. A 2011 paper by Neil Z. Miller and Gary Goldman, published in the journal Human and Experimental Toxicology, shows a correspondence between a country’s vaccination and infant mortality rates. The U.S., with the highest vaccination rate, has the highest infant mortality included in the study. Their tables (images below) showed that as of 2009, the U.S. was the country with the greatest number of vaccines given before one year and the country with the highest IMR.

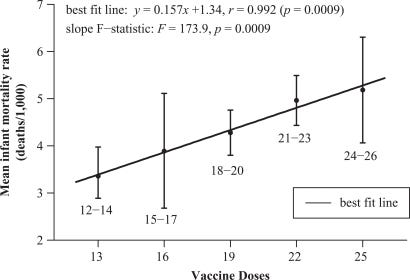

They noted that when countries have provided sanitation, hygiene, nutrition, and other basic needs, reasons for the high infant mortality rate (IMR) no longer exist and other factors must be considered. Their graph below (Figure 2 in the paper) demonstrates the correlation between vaccination and IMR. Countries were grouped based on how many vaccine doses they routinely give to infants, with five categories ranging from 12–14 doses up to 24–26 doses. Then, the average infant mortality rate (IMR) for each group was calculated and compared using a trend analysis to see if there was a pattern between the number of vaccine doses and infant deaths. They did indeed find a positive correlation.

Until vaccinations were required in the 1960s, “‘[c]rib death’ was so infrequent that it was not mentioned in infant mortality statistics.” However, after the vaccines became mandatory in many states to attend school, SIDS became so common that it was introduced as a new cause of death in 1969 and was entered into the ICD as a new death category in 1973.

For the first time in history, most US infants were required to receive several doses of DPT, polio, measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines. Shortly thereafter, in 1969, medical certifiers presented a new medical term—sudden infant death syndrome.In 1973, the National Center for Health Statistics added a new cause-of-death category—for SIDS—to the ICD.

Miller and Goldman noted that even though SIDS does not have specific symptoms, when autopsies are conducted congestion, fluid buildup in the lungs, and inflammatory changes are frequently found.

Although there are no specific symptoms associated with SIDS, an autopsy often reveals congestion and edema of the lungs and inflammatory changes in the respiratory system.

As time went by, this new cause of death became the leading cause of death among infants from 2 months to a year.

By 1980, SIDS had become the leading cause of postneonatal mortality (deaths of infants from 28 days to one year old) in the United States.

The rise and fall of SIDS prevalence

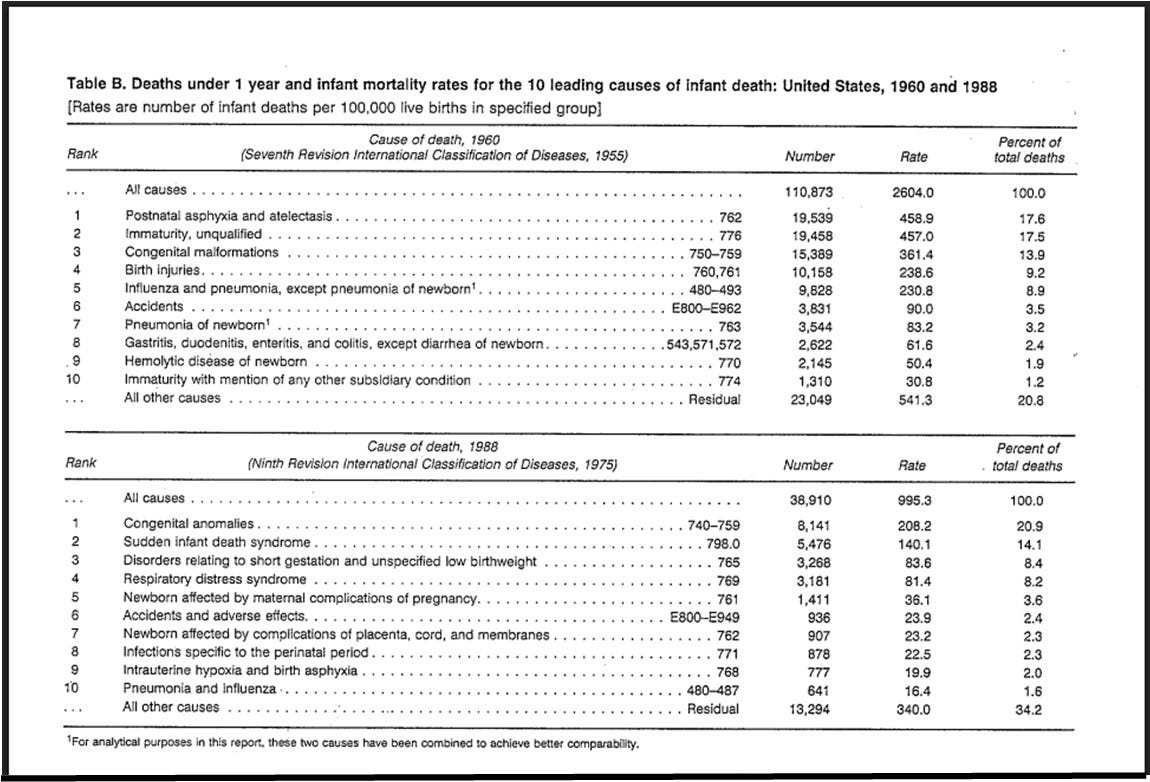

In January 1993, the CDC published “Vital and Health Statistics Trends in Infant Mortality by Cause of Death and Other Characteristics, 1960-88.” It included two tables (page 10, image below) showing the top 10 causes of infant death in 1960 and 1988. Note that the disease classifications in 1960 utilize the seventh revision of the international classification of diseases from 1955, while the 1988 table utilizes the ninth revision from 1975. and includes SIDS (identified as a distinct cause of death in 1973, as mentioned above) in the second table. It was noted that the eighth and ninth revisions were substantially the same.

The CDC report described the autopsy findings mentioned by Miller and Goldman, with the addition that “[i]n the majority of cases, minor intrathoracic petechial hemorrhages,” small spots of bleeding inside the chest, are found. These findings led to the categorization of SIDS as distinct from other unknown causes.

Because of these characteristic features, experts and researchers in the field consider SIDS a clearly identifiable distinctive entity even though the cause and mechanism of death remain unclear.

» » Why is it that authorities claim to have ruled out vaccines as a causal factor but can’t identify an actual cause for such clear damage?

Decreasing SIDS cases by changing criteria?

In its October 1996 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), the CDC discussed SIDS data from 1983-1994. By 1994 it had dropped from being identified as the second leading cause of postneonatal mortality to the third leading cause.

Some of the drop might be explained by shifting definitions for SIDS deaths. The agency explained that the definition of SIDS was made more specific in 1991, requiring not only an autopsy but also an investigation of the death scene, a change that may not have been implemented uniformly throughout the country.

Before 1991, only an autopsy was required for the diagnosis of SIDS. During 1991, the official definition of SIDS was revised to require an investigation of the death scene, although this change may not have been uniformly implemented by all state/local health departments.

The agency contends that the change in diagnosis had nothing to do with the large decline in the SIDS rate from 1990-1994, even as suffocation and other ill-defined conditions increased.

However, because the non-SIDS postneonatal mortality rate did not change substantially during 1983-1989 and 1990-1994, a shift in diagnosis probably did not account for the larger declines in SIDS during 1990-1994. The occurrence of related diagnoses such as suffocation (ICD-9 code 913) and other ill-defined conditions (ICD-9 codes 780-797 and 799) increased from 1983-1989 to 1990-1994 (28.8% and 29.2%, respectively), but these diagnoses combined comprise less than 1% of all infant deaths.

The agency had also included a category of sudden unidentified infant death (SUID), as a catchall category for total infant mortality. The agency’s webpage, “Trends in SUID Rates by Cause of Death, 1990—2022,” includes the following graph which shows that while SIDS rates appear to be decreasing, death from accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed and other unknown causes is increasing.

Is it possible that the inclusion of a death scene investigation as a requirement for identifying the deaths as SIDS was responsible for the appearance of a precipitous drop in SIDS deaths? The failure of this change to be “uniformly implemented by all state/local health departments” puts the veracity of these figures into doubt. Discounting deaths without an investigation at the scene would also account for the unexplained sudden increase in asphyxiation and unknown causes.

» » Is a death that bears the telltale signs of SIDS at autopsy not a SIDS death merely because an investigation of the death scene was not conducted?

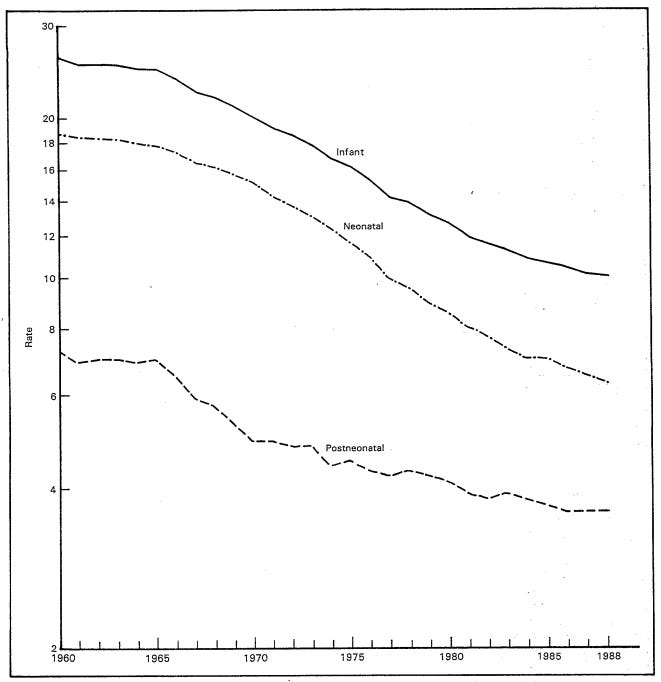

Infant mortality had already been declining since at least 1960, as shown in this CDC graph from the Vital Statistics document (page 5). This raises the likelihood that some of the decline from 1990 to 1994 may have been part of the same downward trend, perhaps related to improvements in maternal and neonatal health care and improved nutrition.

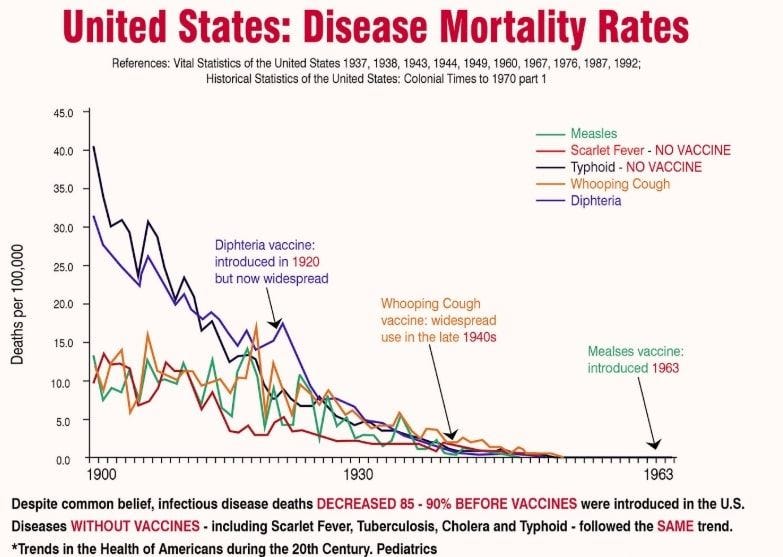

As The Gold Report news site noted, childhood illness-related infant mortality had already dropped by about 98% before vaccines were introduced. The following graph illustrates this trend.

» » If the mortality rates from all illnesses, including ones for which vaccines were not developed, fell so substantially, why was there an insistence that infants be vaccinated?

What other methods have scientists and health authorities used to reduce the number of SIDS cases, especially in light of the autopsy findings? Part 2 of this article will review the results of the back-to-sleep and safe-to-sleep campaigns initiated ostensibly to reduce the risk of SIDS, the lack of good science when it comes to researching SIDS, and further evidence that it may be vaccine-related.

Related articles:

The information contained in this article is for educational and information purposes only and is not intended as health, medical, financial or legal advice. Always consult a physician, lawyer or other qualified professional regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition, health objectives or legal or financial issues.